By: Elona Michael

This fall, the McMullen Museum’s third floor features an exhibit consisting of fifty-five digital prints taken by Nobel Prize-winning chemist Martin Karplus during his travels across Europe and North America in the 1950s and 1960s. Known for his groundbreaking work in developing computer-based models for complex chemical systems, Karplus managed to defy expectations by also pursuing his deep passion for photography. Through taking a multitude of photographs, meeting people from all walks of life, and drawing on his personal experience that shaped his strive for exploration and academic curiosity, Karplus’s exhibit and life’s work truly encapsulate the bridge between science and art, in addition to the art of being human.

At the young age of 8 years old, Karplus and his family fled Nazi-occupied Austria for the United States following the arrival of German forces in 1938. Leaving everything he knew to live in a foreign land, he found himself drawn to chemistry during his time at Newton High School. It was from there, Karplus attended Harvard University for undergrad, and eventually Caltech for his doctorate program. Following his graduation from Caltech in 1953, his parents gifted him a Leica camera, and that is where the magic started.

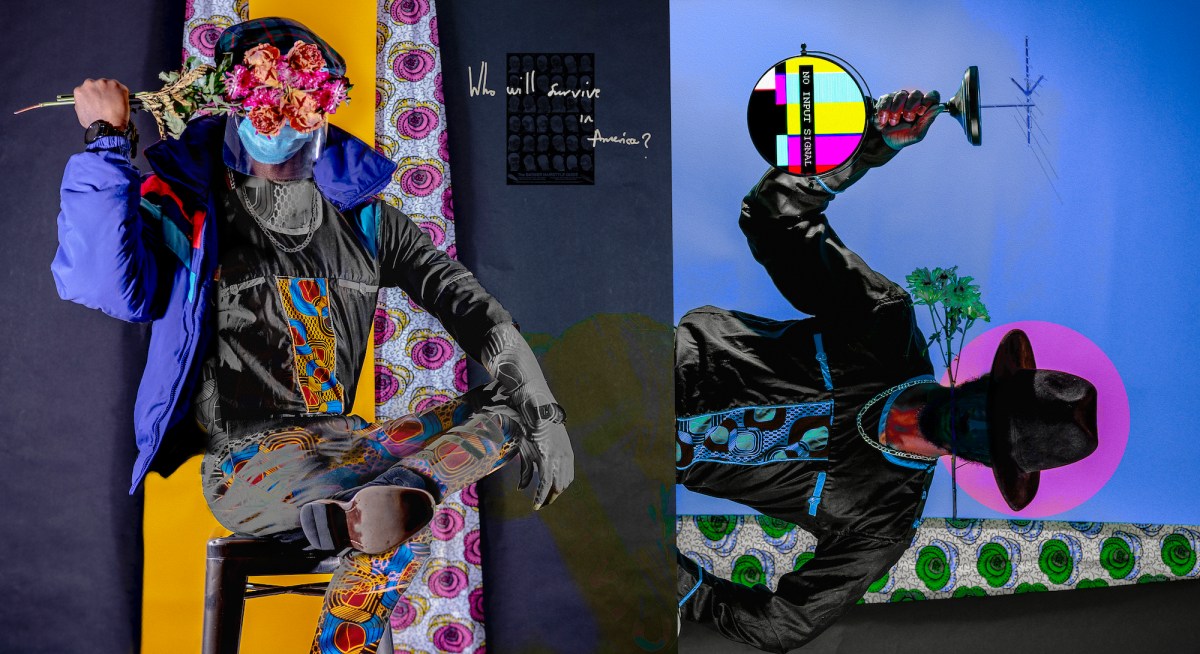

During his postdoctoral fellowship studies at Oxford at 23, Karplus utilized this opportunity to step away from his traditional academic schedule and take photos during his travels. With just a Volkswagen Beetle and his camera, he was able to capture vast cultures, everyday people, beautiful architecture, and authentic cuisine. And in a post-World War II and Cold War society filled with growing sentiments of competition and disconnection, Karplus’s documentation served as a rich portal, highlighting the reconstruction and resilience of different societies during this time period, focusing on fundamental human emotions and connections.

Decades later, in 2013, Karplus received a Nobel Prize for his research efforts toward the development of multiscale models for complex chemical systems. Because of his lifelong commitment and curiosity for chemistry, from receiving his first Bausch and Lomb microscope as a teenager to his later study of the bifluoride ion, he was able to utilize this pursuit and later transfer it into his photography journey.

In 2015, Karplus gave back to his country of origin, exhibiting his groundbreaking collection in the Austrian embassy in Washington. Guests were greeted by his photographs from all over the world. His collections feature vivid pops of color paired with incredible interconnected relationships between landscapes and people. For example, one of his collections features schoolgirls walking in a line with bright pink skirts in Rome, Italy, and another shows Diné men sitting and smoking cigarettes in a doorway in Gallup, New Mexico.

These symbolic messages presented sentiments of hope and despair, youth and old age, and quiet and loud. But most importantly, it captured the simplest yet universal qualities of human nature. Karplus’s precision to detail alongside his lifelong efforts of curiosity, science, and observation allow him and the vast viewers of his works to explore the everyday moments and indulge themselves in the lives of others.

Right before he died in 2024, Karplus and his wife gifted 134 digital prints of his photography to the McMullen Museum. Now, they stand ready to be viewed by students and professors at BC and beyond, living out Karplus’s legacy of crossing borders, documenting and observing the diverse world around us, ready to be explored.