Lauren Whitlock ‘24

Drake DiPaolo, a twenty-year-old passionate about museums—and a McMullen Student Ambassador—was ecstatic to see four older people enter the gallery. They appeared frustrated by the video on the far side of the room. In their faces, you could see them asking, “Is this the last one?” as they sat down on the opposite side of the room and began to speak loudly to one another. This room was on the third floor, and on the second was the Barjeel Art Foundation’s show Landscape of Memory, which displayed seven videos focused on the “rich and complex history of the Middle East.” Naturally, the people assumed that this floor would have more of what they had just seen, videos. But this space was a bit different. The room was cramped, with vertical LEDs glaring and dark walls. Exhausted by the exhibit, the viewers discussed how all the videos were about death, and none of them had been in English. Confused, they looked at the people in the video dead in the eye. But, something felt eerie about the figures, as if they were watching the visitors. Drake walked over.

“It’s actually like a zoom; these people live in a refugee camp.” The visitors spent their remaining time at the museum complaining that they could not hear the people, understand their accents, or even comprehend the point of the exhibit. They made sure to tell me this, the worker at the front desk, on their way out. This uncomfortable scene comes from a semester of bizarre interactions between visitors and “the Portal” at the McMullen Museum of Art from January 30th through June 4th, 2023.

When I initially heard about the exhibit, the concept of the portal also confused me. I found the name dystopian, fantastical, maybe something out of a Back to the Future Movie. What the hell was the Portal? A Portal to where? Was there more than the video art installations on the second floor? But, on the third floor, there was more: a small room with all-black walls, about 12 chairs, and a video projection. The Portal was unlike a Delorean and had no time or space travel capabilities; its goals were much more advanced.

I later learned that “The Portal” is not unique. It is a room-sized audio-visual experience providing a cross-continental connection you can place on any college campus. The proprietor of the technology and licensing, Shared Studios, has a clear Silicon Valley-esque message of connection. Their website displays a picture of President Obama and his words while using this portal: “It’s an amazing technology, making it seem like you are standing right in front of me,” he says while speaking to young entrepreneurs from Iraq. Topics of conversation vary, from climate change to artistic expression, but the overarching theme of cultural exchange is consistent throughout.

Now that it was at the museum, patrons and BC students could connect with people from all over the world. Specific topics were encouraged for certain groups. For instance, a group from Barbados talked with a professor and their Oceans class about climate change. A group from the Nakivale refugee group was encouraged by Shared Studios to discuss the portal they built out of bottle bricks. A group from Palestine discussed their futures. Many of them reflected on the current exhibit’s Landscape of Memory’s themes of exile, home, war, and family. The audience was never as diverse as the speakers featured at the Portal. Throngs of white college students entered the museum. They had to write papers on their experience—how were their eyes fully opened? Many of the participants were young college students mandated to be there to meet someone different from themselves. Most would sit there dead silent, hoping to get through the event and get their extra credit.

In comparison, Drake spent countless hours worried about the Portal and its functions. He would come early to work to set it up, go into every connection with notes on discussion topics, and encourage visitors around the museum to join him. Despite his best attempts, he was the only one willing to put in this effort. Drake recounts moments where he felt like he was pulling teeth; “at times, I felt like I was running a circus. It was hard to manage the people in the room. Sometimes, they would just sit and watch whoever was talking. You had to force interaction.” The placement of the exhibit itself was bizarre. There was a video installation in another part of the exhibit, implying to visitors that this, too, was something to view. “It was also weird because they are having this interaction, but in the room right next to them is the rest of the exhibit,” Drake said. There was a feeling that museum-goers should view these people, their stories, culture, and even trauma as objects.

Though conversations that took place in the Portal are essential to understanding one another, to have these conversations within the context of a museum space reinforces power structures. The museum has once again become the playground for people with wealth and power. The people on the other end of the connection are often othered by this experience. Though they are involved in this process, they are the ones on display. The first time I saw the Portal, I was reminded of the historical display of others. I had recently taken a class in Victorian studies and was eerily reminded of their practices. The purpose of the museums in the Victorian period was to display so-called conquered cultures from across the globe. Indian silks and bead-work were an essential feature of the museum. The museum became a part of the nationalistic rhetoric and colonial projects.

The Victorians are also responsible for developing freak shows and human zoos in the late 18th and early 19th centuries to display people with non-Euro-centric features and disabled bodies. Pseudo-science and the academic field of anthropology reinforced these backward forms of entertainment. The basis of science and historical study justified false racialized narratives that pervaded museum exhibitions for the public to view. The “other” was put on display for societal purposes. Museums became a place where the “other” is reminded of their place, and the audience is reminded of their superiority. These interpersonal interactions reflected the colonialist tendencies of Great Britain and other European powers. Viewers mocked, laughed at, and, in some cases, attacked the subjects of the human zoo.

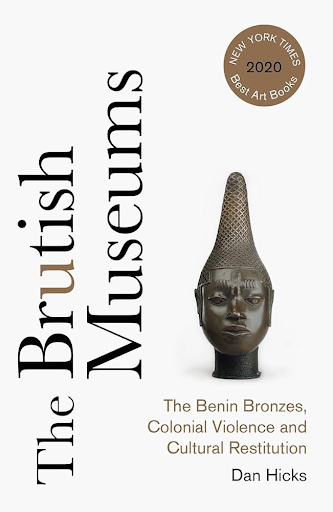

Dan Hicks, in his book Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution, describes the “second shot” produced by museums. The “first shot” is the colonial exploitation and theft of indigenous art, and the “second shot” is a continuation of this narrative. Though not entirely the same as a human zoo, the McMullen Museum’s Portal continues the “exhibitory” gaze of the past. Through the Portal, the museum puts the “other” on view. Not only are their bodies on display, but their trauma is now a learning experience for others. The Portal accentuates power differences when watching the conversations, and there is also something Foucauldian about the museum entering these people’s homes. The Portal is an installation meant to connect people, but it has created an exploitative environment in practice. There is constant surveillance of the “other.” Museums have always struggled with this issue. New technology does not break down the old power structures. Exploitation does not need to be at the root of art.

Drake left the interview with a few words, “You can’t view it as an exhibit.” Context is important. In the museum’s attempt to diversify and enrich experiences for their visitors, they exploited the lived experiences of people in countries with fewer opportunities than the US. Yet, exploitation is a conscious choice made by the visitors. A random student who has done nothing to learn about the Portal speakers enters the space differently than someone with the intention of discussing difficult topics. One student, Ashley Shackelton, who participated in a Portal on campus, not in the museum, felt that the experience was necessary to her learning. “It felt like we had to have serious academic conversations if you went with a class. But my favorite most meaningful conversations were about sharing music and books we found inspiration.” We can still meet the goal of the Portal—human conversation—if the person with the power in the transaction is willing to absolve themselves of it. However, Ashley noted that the connection felt blocked by the technology. She notes, “there wasn’t much comfort I could provide… It reminded me that although we could have incredibly enlightening and important conversations, we were still speaking through a video.”

In attempting to create human interaction, Shared Studios is placing the importance on both groups of people coming together as equals to have a discussion. Reality is not as simple. The conversation is not on an equal playing field in a space of power such as a museum or a college. Some of my discussions in the Portal were constructive and opened my eyes to new experiences. Drake recalls a moment when the translator had not yet arrived, and a class of students blankly stared at the people on the screen. In a moment of panic, Drake posed the question- Messi or Ronaldo? Everyone in the room understood what was happening and interacted despite the language barrier. Drake is a shining example of how to make this technology work.

The idea that we are all similar no matter what is true, but understanding differences allows for richer and more empathetic conversations. Historical and present contexts affect these interactions. The only way to move forward is to acknowledge our differences while learning our similarities. In this way, the Portal can work.

Works Cited

Dan, Hicks. The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution, Pluto Press, 2020, pp. 152–65. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv18msmcr.17. Accessed 22 Mar. 2024.

Bennett, Tony. The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics. Routledge, 2005.